Three by Three: Guest Artists in Focus

QUESTION 2. Your photography often feels quiet and contemplative. What tells you that a moment is worth preserving—not because it’s dramatic, but because it holds something unresolved or lingering?

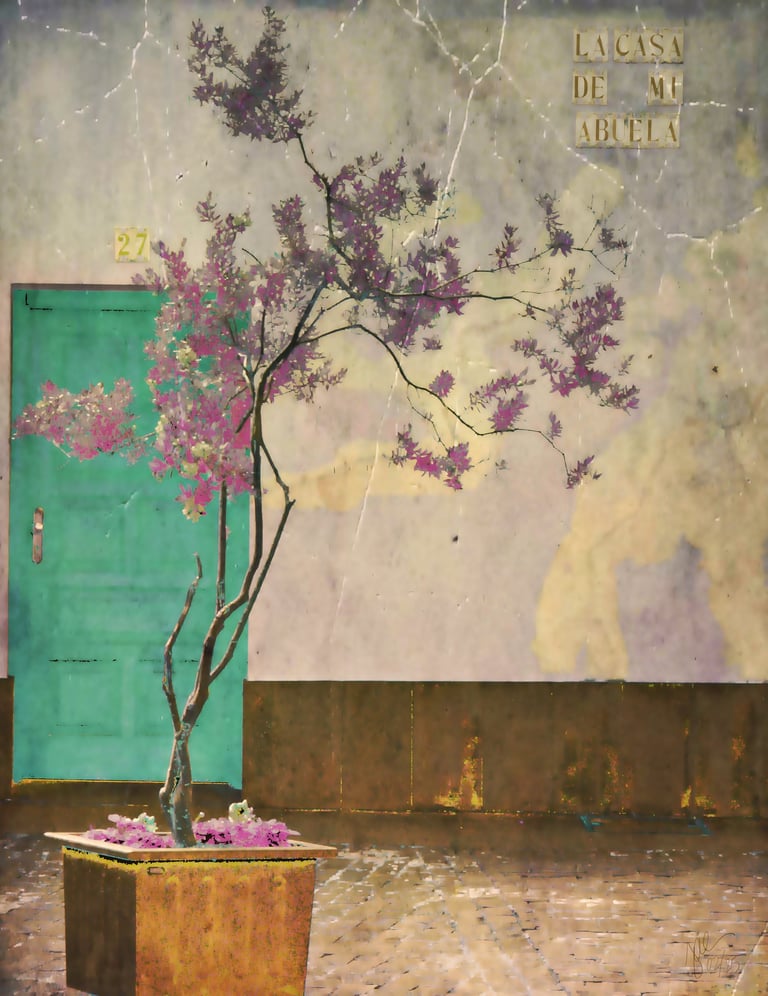

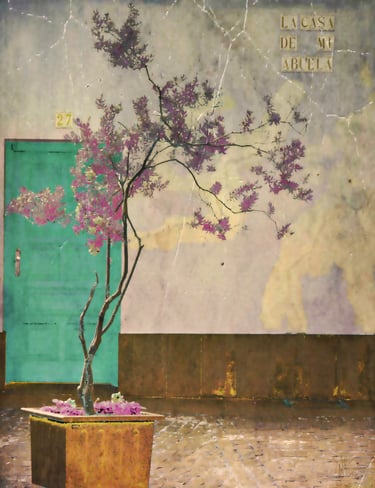

ANSWER 2. I photograph things that catch my eye—a color or a shape, the way the light reflects on an object, or something small and unobtrusive that resonates with something in my life. Sometimes I wonder whether these triggers somehow call to my subconscious, ask to be photographed and preserved. Time moves on, things—people, objects, events—become lost to history. Except when I photograph them. In La Casa de Mi Abuela, it was the tile letters near a beautiful brown wooden door on the side of a building on a back street in Santa Brígida on Gran Canaria. The door stood out against the old cracking, unpainted wall, and a potted tree was the only decoration, the only spot of color. Without these tile letters there was no way to identify this otherwise inconspicuous place as a home. My grandmother’s house was just a house, but inside it was always a welcoming and comforting place for me growing up. I loved the idea of announcing a feeling for a place in this way. My computer contributed to my being able to represent this feeling; a tool I admit that often makes my art accidental. While the door itself signals entrance into a space of safety and comfort, using software to make it green allows me to speak also of growth, harmony and luck; green doors specifically are perceived as welcoming. The potted tree as an element represents harmony, completeness and unity; the emphasis on the purple buds signifies peace, mystery and magic. There was no sun that day, no shadows, which meant that I needed to place myself squarely on the scene in order to avoid distorting it. But this too, worked toward understanding what drew me to this photo. The loss of dimensionality in the piece perfectly associates with any memory of my grandmother and the sense of loss I feel to this day. Finally, aging my photos, adding cracks and tears and discolorations, puts them back in a realm to which I believe they belong, and, as Martin Heidegger’s theory of gestalt teaches, to a place of “being”.

Jae Hodges

Art Photographer / Author

MEDIUM: camera, computer, paper

BIO: I am Jae Hodges, Artist: Author, Photographer, Genealogist and World Traveler. From the central gulf coast region of Florida, I express myself using each of these elements alone or in tandem with the others. Genealogy was a gift given to me by my grandfather, love of travel a gift from my grandmother, and the number of stories available to me from both is endless. These tools help me capture and record these stories. I started photographing in Virginia in 2007, I published my first book in Alabama in 2020, and it took an artist’s and writer’s residency in France in 2024 to show me that digital art is only just another exciting path to storytelling. While I deal exclusively in truth, I like to think I see it from the perspective of 360o.

WEBSITE: SomethingToSay

QUESTION 3. Writing and photography handle truth differently—one interprets, the other records. How do you navigate that tension when both are part of the same creative life?

ANSWER 3. Eudora Welty famously worked in both the mediums of photography and writing. While she claimed that the two were, for her, parallel and not directly connected, she also said that making pictures taught her that “every feeling waits upon its gesture”, that being prepared to recognize a single moment worth documenting was something necessary to her writing. By taking a photograph, I stop time and capture a single moment, place, person, or scene. This becomes the record. But I don’t stop with just making the picture into a piece of artwork. I research and read and learn about whatever it is that has captured my attention in the photograph. If I truly believe that my attention was drawn there for a reason, then it is incumbent on me to understand why, and what I’m supposed to gain by it. The photo “Covesea” is an example of this. I was wandering down by the old riverbed in Portree on the Isle of Skye when I spotted several apparently abandoned boats mired in the sand and the muck and the weeds, leaning haphazardly, paint worn off and tarps hanging askew. The idea of abandonment and a return of man, in all his follies, to the sea or earth is a concept that I’ve explored many times with my camera. I didn’t notice that one of the boats was named “Covesea” until I began to work with it. This name had been significant enough to the boat’s owner for him to paint it on the side of his boat. It meant something; it was important. So, I began to research it. Pronounced Cow-see, this name also refers to a series of sandstone caves, accessible only by boat, located on the south shore of the Moray Firth, between Burghead and Lossiemouth in north-east Scotland--to the east of the Isle of Skye on the opposite shore of Scotland. In prehistoric times, these caves appear to have been considered as liminal spaces caught between worlds. Perhaps the man, a fisherman, had originated on the shores of the Moray Firth, and perhaps he had come to the Isle in search of a better living. Perhaps his ancestors, and mine, are represented in the human remains that have been found in the complex of caves. The Late Bronze Age, to which the remains have been dated, defies the ability for any genealogical research, but I’ve long considered that history is a degree of fiction in and of itself, and this would make a great outline for short story into which I can pour the details and knowledge and understanding and interpretation.

QUESTION 1. In The Rose and the Whip, history is carried through intimate human courage rather than grand events. What draws you to centering everyday people when working with historical material?

ANSWER 1. Ordinary people do extraordinary things, and because history is selective these ordinary people, and the events that shape their lives, are often lost or forgotten. The internet is rife with mentions of Lidia Wardell, her arrest for walking naked through the Newbury Meeting House, and her public whipping in 1663. This is all history remembers of this courageous woman, and many historians have even questioned her sanity. When I looked deeper, I found years of systematic persecution before this grand event and after until she and her family were finally run out of the colony. The abuses they endured, and the courage she exhibited, told me so much more about her than those few minutes. This was the story worth writing. I’m currently working on a story about a murder that took place in New Mexico Territory in 1911. I was researching my husband’s great-grandmother and hit an impenetrable wall. She just disappeared, nowhere to be found. Silence. Until I stumbled on a brief mention of her testimony in court that served to convict her husband of shooting her daughter. It isn’t the murder story that interests me, it’s the grief that this young woman endured, largely as a result of her culture, the Church and her family that came to a head with this event and inspired her to break her silence and speak out against them all. It’s often not what happens to us that’s worthy of a place in history, it’s what we do with what happens to us that deserves to be remembered.

Witches of Orquevaux, 2024; Digital Photography; 15x11”; Carrie Dada, Filmmaker

All copyright and reproduction rights are reserved by Jae Hodges.

Artwork may not be reproduced in any form without the artist's express written permission.

CLICK IMAGE FOR FULL VIEW

CLICK IMAGE FOR FULL VIEW

CLICK IMAGE FOR FULL VIEW

La Casa de Mi Abuela, 2025; Digital Art; 19x14”

Covesea, 2025; Digital Art; 18x16”